The Free Fuel of Will

The world was different once. Dragons soared in the skies and aided the kingdom of man. The Empire prospered, magic was in a time of renaissance, the Imperial army kept peace and order throughout the realm, and the Dragoknight Legion at its head was beloved by all. So it was for an age.

That age has died.

Pride and apathy seeped into the ruling hearts of the Empire, like a slow venom, which poisoned man’s bond with Dragonkind, and eventually, sundered it entirely. The once-honored Dragoknight legion is scattered, scorned and abandoned by its people. The hearts of the Empire are torn between ancient magic and new technology. The roads and wilderness are no longer safe as the army which once policed it has dwindled or been replaced by little more than mercenaries of the crown.

In this time of weakness and uncertainty, an unknown evil gathers its forces. In this time of conflicting ideology, the old places of magical power grow tainted. While the crumbling sound of the Empire’s torpid fall goes unheeded by rulers consumed with their own egotism, all manner of foul creatures freely plunder its villages. In this new and desperate age, man’s most powerful allies slumber, and only one hope remains.

But who can awaken the Dragons?

From a Solitary Beginning

That is the teaser for The Quest for Gemstone Dragon, written by yours truly, as is 80% of the game. The game concept, core conflict, goals and storyboard was the brain child of Konstantinos Evgenidis, videogame publisher extraordinaire. My job was to edit and rewrite what he had then add the majority of the game’s text and script including descriptions for the magical and non-magical equipment, and, most importantly, create a sensible narrative that is engaging to Role Playing Game enthusiasts.

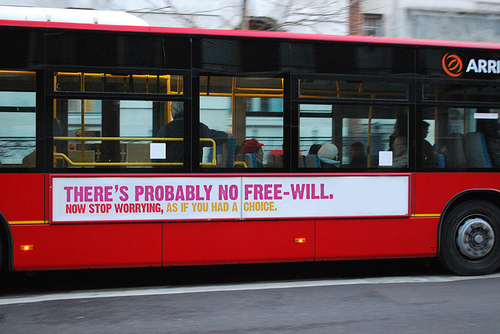

Putting the already awesome pieces together was a fun challenge. Fostering engagement was the trick. According to neuroscientists, gamers, and therapeutic clients are being needfully tricked since free will is a great part of what makes a video game, and therapy, engaging. Gamers need to feel that they have choice in Gemstone Dragon, and in many linear RPGs of its type. Clients, no matter if they are committed by the courts, by their parents, or just walk in off the street, need to feel that they have free will and that their choices matter. It is crucial to any change-based therapeutic model.

However, “a large body of neuroscientists” staunchly state that free will as a whole “is false, or at best an illusion,” according to Dr. David Rock, of the NeuroLeadership Institute. He believes that the true issue is not if free will exists, but if the belief in it is beneficial to clients. I believe that we don’t trick our clients as therapists or video game writers by fostering a belief in free will since much of its “existence” stems from the participants perspective of personal control. Free will is real, on a macro level. Both gamers and clients have the big, ultimate choice—they can put down the controller or walk out of the session. They can turn off the console or end the relationship. Within the game, and within that therapeutic relationship, the choices grow more limited, if the participant wants to get to their positive end, be it successful discharge or the game’s “Happy Ending.”

The Ever Twisting Path

The challenge with building a feeling of free will into the narrative of a linear RPG like Gemstone Dragon was that it has one beginning and one end. This is the classic RPG style. However, for the game to be truly engaging, the player should feel some form of “emotion, purpose, meaning, understanding and feeling,” as David Perry, of Earthworm Jim fame, said was the primary focus of game developers. The same experiential goals are key to a beneficial therapeutic process.

The challenge with building a feeling of free will into the narrative of a linear RPG like Gemstone Dragon was that it has one beginning and one end. This is the classic RPG style. However, for the game to be truly engaging, the player should feel some form of “emotion, purpose, meaning, understanding and feeling,” as David Perry, of Earthworm Jim fame, said was the primary focus of game developers. The same experiential goals are key to a beneficial therapeutic process.

I tried to achieve it in Gemstone Dragon by ensuring that the choices the player made, even if just in dialogue, were as diverse and impactual as possible, by tailoring strong emotive reactions into the NPC responses, or lacing the scene text with an internal dialogue which related to the choice just made. Konstantinos also prioritized the concept of free will in games. Though there was only one path through Gemstone Dragon, the player had some choice in how to travel that path, in what order to complete the missions, and even a few secret areas which the player could find by stepping off the path. Was it still free will if “stepping off the path” still led to the same end? I’m with Dr. Rock, the existence of free will on a philosophical level is irrelevant to the beneficial impact of the feeling of free will.

A study by Dr. Roy Baumeister of Princeton University found that a belief in free will increases a person’s performance, and their confidence in their continued performance. Therefore, a belief in free will “facilitates exerting control over one’s actions.” Many of my clients lack this belief in their own will, and a strong component of success is enabling them to see the control that they have over their own actions within treatment, even if they lack current control of their larger legal situation. Similarly, games in the Final Fantasy series—though linear—are designed in an “hourglass” format in which linear segments of the game forward the plot and open up “wider” segments which allow players to roam and complete mini-missions.

A Single Motive, A Single End

There have also been studies like another by Baumeister and a joint study with the Psychology Department of the University of British Columbia which strongly link a belief in free will to increased personal satisfaction, increased empowerment, lessened aggression and lessened tendency toward deceitful behavior. That is practically a recipe for successful treatment of many social maladies. Also, while not curbing my aggression, I can say that the feeling of empowerment and freedom found in two of my favorite RPGs, Bethesda Softwork’s Oblivion and Fallout, increase my feeling of personal satisfaction, hardly ever provoke me to cheat. and most of all, Both offer so much perceived “free will” that, regardless of their single main ending, they become frighteningly addictive and enjoyable games.

The debate over the existence of free will shall rage on as science continues to advance in its ability to study the handiwork of He who thought up free will in the first place. We, writers as the little gods of games, or we therapists who walk along side of our clients on their paths can best serve our charges by empowering their perception of free will, regardless of its existence, since the power of that freedom is what fuels the will.

K