The Tool Within the Tool: Our Office, Ourselves

“Today in America it is almost heresy to believe that the roots of thought have any importance.” –

– Dr. Gregory Bateson, Author

We do countless different things, in many different spaces, every moment of our days. But we all, at the root, do one universal thing all day; we think. We process information. While the direct focus here is on how we can use our constant information processing in designing an ideal therapeutic space, it can also be applied to increasing the enjoyment, health and productivity of any space, because it all starts at the same root; thought.

“Information can be defined as difference that makes a difference” and a mind as an elegant tool which interprets, describes and defines that information while also “through self-regulation or self-correction…maintains the truth of certain propositions about itself” (2004). These are the words of Dr. Gregory Bateson and his daughter Dr. Mary Catherine Bateson, who builds on her father’s work in exploring how the elements of the world interact with one another, now that he has died.

When his exploration began, Bateson borrowed two terms from psychiatrist Carl Jung and applied them anthropologically; Pleroma and Creatura. Pleroma is a word for “all non-living matter,” Creatura is a word that encompasses organic life, systems, minds and most of all, the relationships between these things. In digesting Creatura think not of the root word “creature” but of the root “creator” because Bateson placed great emphasis on the belief that all of the non-living world exists within our definition of it; thus we essentially create the world around us using our minds’ interpretation (Bateson & Bateson, 2004).

When you break a room, like an office, down to its essence it is simply information that is interpreted by our mind. It is difference with a difference but with a purpose, because we of Creatura can’t help but define that office by our own relationship to the material in it. Therefore, as a therapist, our office is our first intervention with our patient, and the continuing intervention. But, it is also the space in which we operate, therefore, it must also be the most stimulating and sustaining environment for us to hone and perform our craft.

“In fact,” according to environmental psychologist Dr. Tobi Israel, “every therapist’s space provides the backdrop against which clients’ personal dramas will be revealed. Yet, psychologists typically receive little, if any, training about how to set an effective stage for the client-practitioner interplay” (Israel, 2010).

Sharing the Purpose

“I could not let myself be stared at for eight hours daily.”

-Dr. Sigmund Freud, on why he put his chair behind his patients’ heads.

Dr. Toby Israel is a pioneer in designing spaces that serve proposes—spaces that are tools themselves, which can elevate how any task is enjoyed and achieved; from psychotherapy to  watching a movie, to making a meatloaf* in a mindful kitchen. The observation made by Bateson that, “all of Creatura exists within and through Pleroma [but] on the other hand, knowledge of Pleroma only exists in Creatura” describes the interplay that Dr. Israel is able to use like a tool that envelopes and elevates the purposeful work within (Bateson & Bateson, 2004).Yes, it’s a heavy thing; but at its root, it’s simply that we create the space in which we create. The better we design the space in which we work, the better our relationship will be with that space, the better the end product will become. “Thus, [therapists] can consciously create a space with positive (even therapeutic) benefits for their patients” (Israel, 2010).

watching a movie, to making a meatloaf* in a mindful kitchen. The observation made by Bateson that, “all of Creatura exists within and through Pleroma [but] on the other hand, knowledge of Pleroma only exists in Creatura” describes the interplay that Dr. Israel is able to use like a tool that envelopes and elevates the purposeful work within (Bateson & Bateson, 2004).Yes, it’s a heavy thing; but at its root, it’s simply that we create the space in which we create. The better we design the space in which we work, the better our relationship will be with that space, the better the end product will become. “Thus, [therapists] can consciously create a space with positive (even therapeutic) benefits for their patients” (Israel, 2010).

But there’s a balance in that; a shared purpose to therapy. I have been criticized—rightly so—for being a selfless therapist. I’m very much about the work and helping my patients do it. However, I neglect to think about my office as my space, too. But, our patients wouldn’t need us if it wasn’t for the skills we have. If we don’t ensure that the environment is the best possible place for us to use our skills and they to do their work simultaneously, then we’ve not done the job well. Dr. Isreal starts here first. “Think about your own personal and therapeutic style,” she encourages, “What office look and feel would bring you pleasure yet remain open-ended enough to allow your clients to feel secure, comfortable and free to reflect?” (Israel, 2010).

The Power of Pleroma

“The world as we have created it is a process of our thinking. It cannot be changed without changing our thinking.”

– Dr. Albert Einstein, Thinker

The relational aspect of Creatura within Pleroma has been and is still being explored and applied in many design disciplines. Though they come at the same relationship from neurological, architectural or medical perspectives, the approaches are all alike in their acknowledgement that a purposeful environment is one that elevates the experience of both staff and patient at the same time. Inside the tool of an elevated environment staff perform better and patients heal faster.

The relational aspect of Creatura within Pleroma has been and is still being explored and applied in many design disciplines. Though they come at the same relationship from neurological, architectural or medical perspectives, the approaches are all alike in their acknowledgement that a purposeful environment is one that elevates the experience of both staff and patient at the same time. Inside the tool of an elevated environment staff perform better and patients heal faster.

“Evidence Based Design” according to Dr. Nicola Davies (2015), “was at least partially born out of patient-centric evidence-based practice in healthcare ” and is rooted in neuroscience, but it “…isn’t a confining and stagnant template without any room for creativity; it combines both the results of such research and artistic imagination to elevate moods, improve focus, and enhance efficiency” (Davies, 2015).

Evidence Based Design has an older sister in Supportive Design—a long held theory that guides hospital design—both seek to help nurture change by removing it’s natural result; stress. Dr. Roger S. Ulrich, Director of the Center for Health Systems and Design Texas A&M University, has been a proponent of the Theory of Supportive Design for nearly thirty years. In his experience, Supportive Design and all of the similar fields agree “that the potential for environments to promote improved outcomes is linked to their effectiveness in facilitating stress coping and restoration” (Ulrich, 2014). To this Dr. Davies adds the evidence that elevated design is a tool that “can also help caregivers to perform better in their jobs by decreasing stress and dissatisfaction” (Davies, 2015).

Dr. Davies also notes that “Persuasive Design is a relatively new paradigm that takes steps to embed persuasive arguments into physical objects,” It takes the idea that the mind interprets its environment as information and adapts to it “…to instill clients with the motivation to change their behavior” for example, “having seating around a table instead of in front of a television will persuade clients to be more social…while the use of stools or benches will persuade more customers to sit up straight” (Davies, 2015). Persuasive Design is environment as the intervention.

When seeking to design an environment that is both a relaxation tool and an intervention at the same time, we focus on two actions; “…eliminating environmental characteristics that are stressful or can have direct negative impacts on outcomes [then] a significant step further by including features in the environment that research indicates can calm patients, reduce stress, and strengthen coping resources and healthful processes” (Ulrich, 2014).

Making the Difference

“The trouble with having an open mind, of course, is that people will insist on coming along and trying to put things in it.”

– Terry Pratchett, Author, Diggers

It is no surprise that each one of the design sciences found universal themes that are crucial to build a stress reduced change environment for both patient and provider. Here are some concepts and real-world improvements that we can make in elevating the tool of our office and the joy of our space.

“Research has shown that sterile environments can elicit fear, anxiety and stress, whereas natural environments tend to put people at ease” says Dr. Davies “Creating an optimal atmosphere for healing and recovery” for patients while, employees reported higher productivity and wellbeing just by “working in close proximity to plants [which] improves concentration and memory retention…even in high-stress environments” (2015).

These are easily implemented with plants, fountains, nature pictures and especially windows. Every article noted that lack of windows can foster anxiety and depression, but that sunshine and a view of the outside world aided everyone, staff and patient.

Space Stimulates

Dr. Israel (2010) reminds us that “every counselor’s office has two main vantage points: the therapist looks towards the patient; the patient looks toward the therapist. With this in mind, care should be given to choose a layout, style, colors, furniture, window treatments and office artwork/special objects as experienced from these two very different visual perspectives.”

She suggests that “Zen-like calming colors, soothing sounds, soft textures and pleasant aromas can all have a calming effect but remember that “too much clutter may make it hard for clients to focus.”

Dr. Davies, offers a neurological insight in that “the way we perceive spaciousness isn’t founded only on the actual physical dimensions of a place: Lighting, geometry, color, furnishings, and materiality are just a few of the factors contributing spatial perception. Altering the boundaries of a space—like designing cut-out shapes into partition walls to make them more porous—can be enough to turn a “claustrophic” environment into something more comfortable.” She also notes that “one physical dimension worth considering closely is ceiling height. Research suggests that high-ceilinged rooms promote free-thinking and abstract thinking, while people in rooms with 8-foot ceilings or lower feel more confined and become more detail-orientated in their thought processes” (2015).

Dr. Davies, offers a neurological insight in that “the way we perceive spaciousness isn’t founded only on the actual physical dimensions of a place: Lighting, geometry, color, furnishings, and materiality are just a few of the factors contributing spatial perception. Altering the boundaries of a space—like designing cut-out shapes into partition walls to make them more porous—can be enough to turn a “claustrophic” environment into something more comfortable.” She also notes that “one physical dimension worth considering closely is ceiling height. Research suggests that high-ceilinged rooms promote free-thinking and abstract thinking, while people in rooms with 8-foot ceilings or lower feel more confined and become more detail-orientated in their thought processes” (2015).

Control Counts

A Trauma Informed Approach to mental health therapy and to medical healing both highly prioritize patient and staff to have as much of a feeling of control of their world as possible. Dr. Ulrich (2014) suggests “dimmers that enable control over lighting; headphones that allow patients to select music; televisions controllable by individual patients…” and that this feeling of control can also transition to the seating by “providing comfortable, movable furniture that can be arranged in small flexible groupings…that encourage socializing.” There is an intervention aspect to this as well since, “where clients sit in relation to you and to others, may provide you with clues regarding their own sense of attachment, appropriate boundaries and intimacy,” (Israel, 2010).

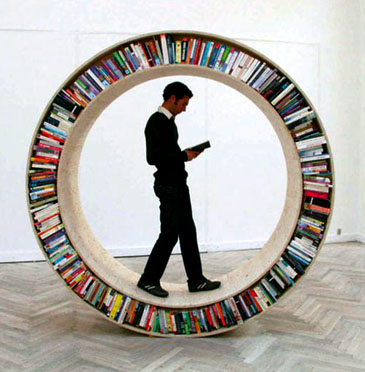

An aspect of control that the authors suggest, and I employ, are various de-stress tools, like stress balls, a Zen garden, mind puzzles and simple toys. Also, I have recently added an anonymous questionnaire about what works and doesn’t work in our shared space that my patients can drop into an envelope to provide suggestions.

Enjoyment is ESSENTIAL

Never forget this one. No matter if making a meatloaf, doing open heart surgery or trauma therapy, the space should be as enjoyable as possible to elevate the work being done. We are the tool within the tool of our office. Though there is much science behind the implementation; we know this stuff already.

Noise is bad, music can be good. Stuff to play with is fun when not distracting. Sunshine through windows reduces anxiety and provide shorter depression stays, but cloudy days made patients and staff sadder—yes, there was a study!

Dr. Israel gives us a wonderful picture as a closing analogy. She knows a colleague whose office “contains a lovely abstract print of a mountainous scene that her patients can view when meeting with her. The print utilizes tremendous depth of field to draw your eye in and upwards towards a breathtaking pink sky. Thus it provides a subtle, positive suggestion to each client: You can move forward, upward, and grow.”

We all must do the same, patient and provider, Creatura in Pleroma.

__________________________________________________

* That meatloaf (Pleroma) is first made in the mind of the mom (Creatura), then she gets out the ingredients, mixes and cooks (the relational aspect of Creatura-Pleroma, in which Creatura provides the meaning for the meatloaf).

Bateson, G. & Bateson M. C. (2004) Angels Fear: Towards an Epistemology of the Sacred. Hampton Press, New Jersey. Retrieved from: http://www.oikos.org/angelsmental.htm

Davies, N. (2015) Evidence Based Design: When Neuroscience, Psychology, and Interior Design Meet (Part 1 and 2). Interiors and Sources. Retrieved from: http://www.interiorsandsources.com/is-interior-design-blog/entryid/324/evidence-based-design-when-neuroscience-psychology-and-interior-design-meet-part-1.aspx and http://www.interiorsandsources.com/is-interior-design-blog/entryid/326/emotional-and-behavioral-responses-to-interior-design-part-2.aspx

Israel, T. (2010) The Incredible ‘Shrinking’ Office: An office where design and the therapeutic process are attuned? Design on My Mind. PsychologyToday.com. Retrieved from: https://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/design-my-mind/201011/the-incredible-shrinking-office

Ulrich, R. (2014) Evidence Based Environmental Design for Improving Medical Outcomes. Chalmers University of Technology Retrieved from: http://www.swiz.nl/evidence_based_design_ulrich.pdf