The River’s Secret: Flow through adversity and anxiety

“Of all the virtues we can learn no trait is more useful, more essential for survival, and more likely to improve the quality of life than the ability to transform adversity into an enjoyable challenge.”

– Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi,

Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience

Key: A frozen river still flows.

Living it: Trust in yourself and move forward into adversity with a purpose, a plan and practice.

Clinical Concept: Overcoming freeze-state symptoms or decision paralysis via informed seeking of flow state.

We can learn much from the world around us. Take, for example, this fork in a river on one of my running paths. Have you ever felt like this river? I have. Two ways to go, not sure which one is best, pulled in two directions. The problem is, we’re not like a river. We can’t run both channels; we must choose. That choice can promote feelings of stress or anxiety and for some of us who linger there, it can bring about feelings of depression. For those already depressed even the seemingly simplest forks can bring this on. We freeze.

It’s called decision paralysis; getting frozen by choice and not able to choose. “Being indecisive stems from caring too much about too many things,” Alex Dr. Korb writes in The Upward Spiral. We freeze in these situations because our “goals, habits, fears and desires all compete for limited brain resources” (Korb, 2015). Even the smallest choice can engage many different parts of our brain at the same time and that’s too much, so we don’t choose. When we are confronted with something stressful or worrisome that freeze has more to do an internal choice linked to survival.

Let’s take this view of the creek. It looks much more frozen here. Perhaps you relate to this feeling—an actual frozenness. This feeling fits into an updated view of the Fight or Flight response, first coined in 1927. Research in this century updated two things. First, the action was changed to “Fight, Flight and Freeze” because people don’t just fight or run away when triggered, they also stop. Second, researchers noted that the order is more fluid and resembles “Freeze, Flight, Fight” because pausing to assess the situation is what we do first and most often in most every-day cases, then we may choose to flee, and less often to fight (Schmidt, et al, 2008).

According to the above study in the Journal of Behavioral Therapy & Experimental Psychiatry “data suggested that reports of freeze were more highly associated with certain cognitive symptoms of anxiety (e.g., confusion, unreality, detached, concentration, inner shakiness). This leads to some very interesting speculation regarding whether…a form of cognitive paralysis occurs due to immense cognitive demands that occur” when a person is confronted with something worrying or stressful (2008).

I will step out and say, yes, I believe cognitive freezing occurs and is so common it’s overlooked. Every worried kid who pauses by the school door, every jittery player who needs the “You can do it!” from coach to get into the game, every office person who reads an email about a mistake they made, gets an emergency project from the boss or sees a forgotten meeting on their calendar confronts and overcomes a moment of frozen anxiety. Sometimes it’s brief, for others it’s longer. For those of us who live with depression that momentary frost can become what seems like, and feels like the deepest, most solid winter ice.

The Flow of the River

“Enjoyment appears at the boundary between boredom and anxiety,

when the challenges are just balanced with the person’s capacity to act.”

– Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi

So, how do we come unstuck? What do we learn from the river? Let’s look closer at those pictures.

That river is still flowing, in some places it’s just a trickle, in some places it is fully blocked. The secret of the river is that, when confronted with a choice or stressor, we do what it does and just flow. That is a picture of an actual observable and livable phenomena which was studied by Dr. Mihaly  Csikszentmihalyi in the uber-bestseller Flow. Dr. Csikszentmihalyi was intrigued by artists, musicians, athletes and regular people who get “in the zone” and he examined what it means to be in that zone, that groove, that “happy place” where everything just synchs up and we lose ourselves in the moment. Then he came down from the mountain and shared it with the rest of us to use in our daily lives. “To overcome the anxieties and depressions of contemporary life” he wrote “individuals must…develop the ability to find enjoyment and purpose regardless of external circumstances.”

Csikszentmihalyi in the uber-bestseller Flow. Dr. Csikszentmihalyi was intrigued by artists, musicians, athletes and regular people who get “in the zone” and he examined what it means to be in that zone, that groove, that “happy place” where everything just synchs up and we lose ourselves in the moment. Then he came down from the mountain and shared it with the rest of us to use in our daily lives. “To overcome the anxieties and depressions of contemporary life” he wrote “individuals must…develop the ability to find enjoyment and purpose regardless of external circumstances.”

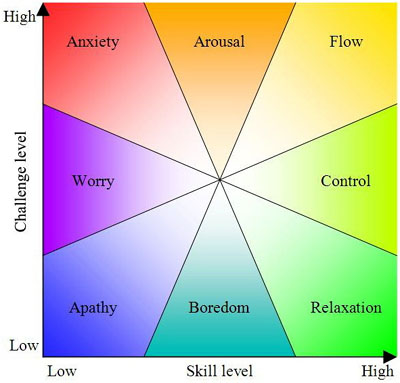

We develop the ability to flow by cultivating within ourselves the ability to handle any situation that may come up river as purposefully and enjoyably as we can. It’s normal to freeze a bit when confronted with a challenge, but under the surface of that ice, we flow. We practice skills that we can rely on in the moment and call them to action, like an athlete, factory worker or parent, and we do that just like the river, striving forward and using that momentum to empower our own skill building. Because, “contrary to what we usually believe” Dr. Csikszentmihalyi said, “the best moments in our lives, are not the passive, receptive, relaxing times…the best moments usually occur when a person’s body or mind is stretched to its limits in a voluntary effort to accomplish something difficult and worthwhile. For each person there are thousands of opportunities, challenges to expand ourselves” (Csikszentmihalyi, 1990). Check out the chart above. The flow state is in the top right at the intersection of challenge and skills. We don’t want to live in a bored state or an over-taxed state and that means crafting a life that balances personal skill with the ability to move from freeze to flow to meet the challenges we’re seeking.

We will face adversity, there will be winters ahead. The secret is not to avoid the winter, but to keep flowing, even if it means slower or deeper—but never let ourselves be stopped—in the certainty of spring to come. When dealing with stress and anxiety, we plan wisely for the bends we see in the river, but most of all we strive past the frozen moment and go with the flow, because in that two things happen. The first is that the anxious symptoms will fade. The second is that when we look back on the experience, we will see only the achievement we made, and it will build our momentum to overcome the next freeze and the trust in ourselves to face the bends in the river that we can’t see coming.

When facing that fork in the river, Dr. Korb offers the same advice, flow on. Simply deciding on a goal literally shifts your brain from the worry gear to the planning gear, which already begins to thaw a freeze. The full flow comes in realizing that “it’s better to do something only partially right than nothing at all” because “recognizing that good enough is good enough…helps you feel more in control” by deactivating the worry gears and engaging flexibility and creativity—which are keys to flow.

When next we find ourselves with a choice to make or an unexpected bend in our day, I hope we remember the wisdom of the river and just flow, overcome and enjoy the ride as best we can.

__________________________________________________

*A note to you all who’ve read this far: To rebuild this site to meet the new, awesome and ever-expanding desires us all and provide quality content, I will now be releasing an article once a month, on the last Friday of the month. I’ll revisit how it went in June and we’ll decide together if it’s best to go back to bi-weekly. Please email or contact me to share how you feel the new monthly format is working for you, since that’s the most important factor in the process. Thank you, always! – Keith

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990) Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. Harper Perennial, New York, NY

Korb, A. (2015) The Upward Spiral: Using Neuroscience to Reverse the Course of Depression, One Small Change at a Time. New Harbinger, Oakland, CA

Schmidt, N., Richey, J.A., Zvolensky, M. & Maner J. (2008) Exploring Human Freeze Responses to a Threat Stressor. Journal of Behavioral Therapy & Experimental Psychiatry. Retrieved from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2489204/

Previous Post

Previous Post Next Post

Next Post